What Is Constructivist Learning Theory? A Practical Guide

Constructivist learning theory proposes a powerful idea: learners aren't empty vessels waiting to be filled with information but are active builders of their own knowledge. Instead of passively receiving facts, children construct their understanding by connecting new experiences to what they already know. It’s about learning by doing, not just by listening.

What is Constructivism? Building Knowledge Brick by Brick

Imagine a child with a pile of LEGOs. They don't just follow instructions; they draw on past creations (prior knowledge), experiment with new bricks (new information), and build something uniquely their own. In this model, the process of trial, error, and discovery is just as valuable as the finished product.

Constructivism shifts education from rote memorization toward an active process of inquiry. Students are encouraged to ask questions, seek answers, and adapt their mental models with every new discovery they make.

A Practical Example: Shifting From Instruction To Exploration

In a traditional classroom, a teacher might explain the concept of buoyancy by writing definitions on the board. The student's role is to memorize the facts for a test.

A constructivist teacher, however, would facilitate an experience. They might set up a tub of water with various objects and pose a challenge: “Which of these do you think will float, and why?”

By predicting, experimenting, and observing the outcomes, children actively construct their own understanding of buoyancy. This self-driven exploration creates a deeper, more memorable grasp of the concept than simply being told the answer.

This hands-on approach turns a simple question into a dynamic lab where kids drive their own learning. For more on how play sparks this kind of insight, explore our guide to discovery-based learning.

To see the difference clearly, here's a quick comparison:

Traditional vs. Constructivist Learning At a Glance

| Characteristic | Traditional Classroom | Constructivist Classroom |

|---|---|---|

| Teaching Role | Teacher lectures from the front | Facilitator guides from the side |

| Learning Process | Memorization of facts | Investigation and discovery |

| Knowledge Source | Textbooks and lectures | Hands-on experiences and collaboration |

| Assessment Focus | Quizzes and standardized tests | Reflective projects and real-world tasks |

| Student Engagement | Passive listening and note-taking | Active inquiry and problem-solving |

This snapshot shows how constructivist environments empower students, shifting them from passive listeners to curious explorers.

The Impact On Educational Outcomes

This shift from passive listening to active doing delivers real results. Educators who adopt constructivist practices often report significant improvements in student comprehension, critical thinking, and retention of complex subjects. At its core, constructivist learning treats every child as a capable thinker and creator, transforming education into a collaborative journey of discovery.

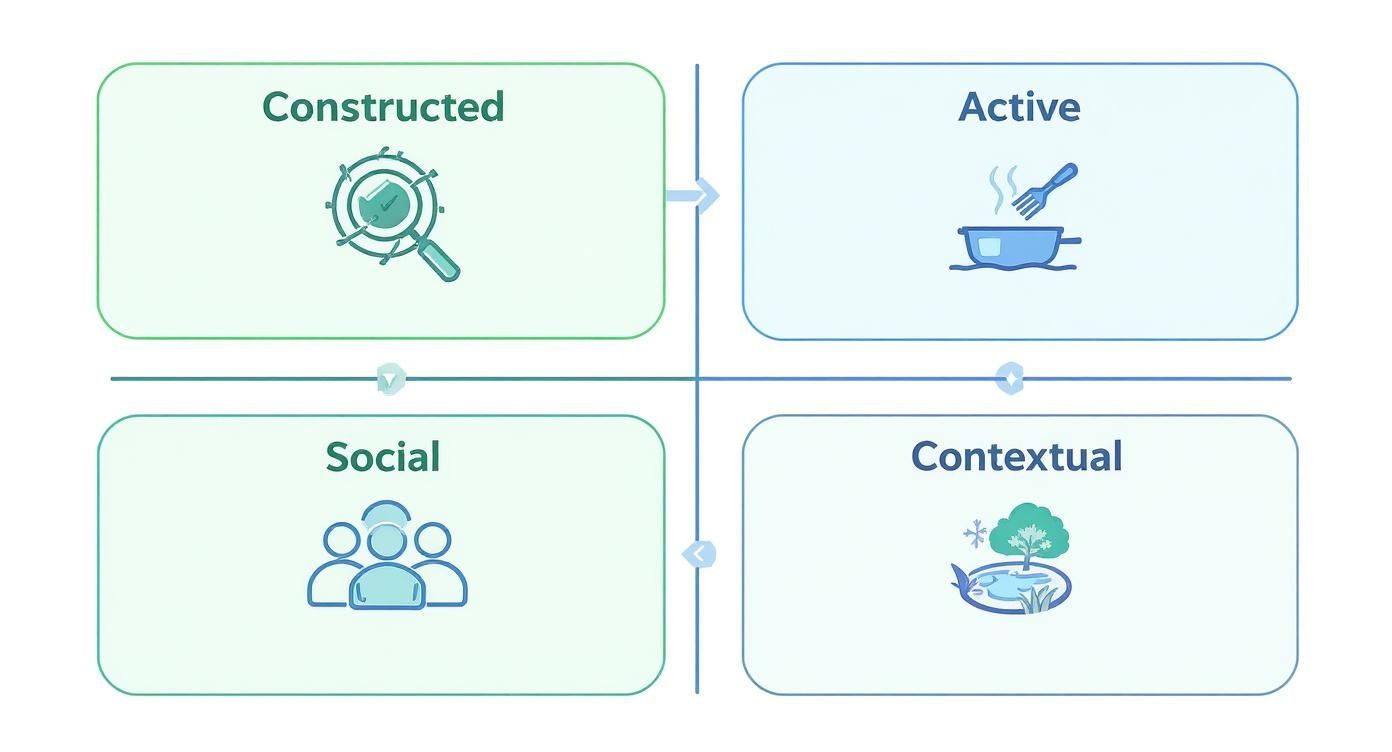

The Four Pillars of Constructivist Learning

To fully grasp what constructivist learning theory is, it helps to understand its four foundational pillars. These core ideas explain how children actively shape their own knowledge, moving beyond simple memorization to achieve genuine understanding.

Each pillar builds on the last, painting a complete picture of how a child's mind engages during the act of discovery.

1. Knowledge Is Constructed, Not Received

The first pillar states that knowledge isn’t something passively absorbed; it’s actively constructed. Children aren't empty sponges. They are more like detectives, piecing together clues. Every new piece of information must connect with the evidence they already have (their prior knowledge) to form a coherent understanding.

Real-World Example: A child learning about dinosaurs doesn't just memorize names from a flashcard. They might read a book, build a model skeleton, and then visit a museum. By linking these experiences, they construct a rich, personal understanding of what a dinosaur was—far deeper than a textbook definition.

2. Learning Is an Active Process

This leads directly to the second pillar: learning is an active process. You can't truly learn to ride a bike by reading a manual; you have to get on and pedal. Similarly, constructivism insists that to learn effectively, students must do something—solve a puzzle, conduct an experiment, or build a prototype.

This “hands-on, minds-on” approach is crucial. When children physically engage with materials and concepts, they forge stronger neural connections, leading to deeper retention and a more robust grasp of the topic.

This is the difference between being told about gravity and dropping an apple to see it in action for yourself.

3. Learning Is a Social Activity

The third pillar emphasizes that learning is a social activity. We don't just build knowledge in isolation. We refine our understanding by sharing ideas, debating different viewpoints, and collaborating on problems. It's like a brainstorming session where one person's thought sparks an idea in someone else, leading to a solution no single person could have reached alone.

Real-World Example: Group projects and classroom discussions are powerful learning tools. When kids have to explain their thinking to a peer or defend their perspective, they are forced to clarify their own ideas and consider other viewpoints. This collaborative process is a vital part of deep learning, and you can explore more about the benefits of play-based learning in our detailed guide.

4. Learning Is Contextual

Finally, the fourth pillar reminds us that learning is contextual. Knowledge makes the most sense when it's anchored in the real world. A lesson on ecosystems from a textbook can feel abstract, but a field trip to a local pond makes concepts like "predator" and "prey" tangible and relevant.

Seeing frogs, insects, and plants interacting in their natural habitat provides a rich context that a diagram on a page cannot replicate. Learning sticks when children can answer the question, "Why do I need to know this?" When they see the real-world application, their motivation and engagement skyrocket.

The Thinkers Who Shaped Constructivism

Constructivism didn't appear overnight. It grew from the brilliant minds of educational pioneers who challenged the traditional model of rote memorization and argued for a more student-centered approach.

The theory's roots trace back to Enlightenment thinkers like Immanuel Kant, who argued in the 18th century that learners are active creators of their own reality. Since then, other key figures built upon that foundation, shaping the principles that guide many modern classrooms. You can take a deeper dive into this history by exploring the foundations of constructivist thought.

Jean Piaget and Developmental Stages

Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget is a towering figure in this field. He revolutionized our understanding of child development by focusing not just on what children know, but how they construct that knowledge.

Through careful observation, Piaget realized that children's brains aren't just smaller versions of adult brains—they operate with a fundamentally different logic. He proposed that we make sense of the world through two key processes:

- Assimilation: Fitting a new experience into an existing mental framework.

- Accommodation: Modifying an existing framework or creating a new one when new information doesn't fit.

Real-World Example: A toddler who has a "dog" schema might see a horse for the first time and exclaim, "Big doggy!" This is assimilation. When a parent gently corrects them, the child's brain must create a new category for "horse." This adjustment is accommodation—and it's the engine of learning.

Piaget’s core insight was that children are not just miniature adults. Their logic is fundamentally different, and they actively build their understanding of the world by interacting with it.

This idea—that learning is an internal, adaptive construction project—is the bedrock of constructivism.

The infographic below illustrates how these thinkers helped establish the four core pillars: knowledge is constructed, active, social, and contextual.

This map shows how individual discovery, hands-on activity, social interaction, and real-world context all come together to create a rich learning environment.

Lev Vygotsky and Social Learning

While Piaget focused on the individual learner, Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky added another critical layer: the social world. Vygotsky argued that learning is not a solo mission but a collaborative one. Our communities, culture, and language are fundamental to how we construct meaning.

His most famous concept is the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). It sounds complex but is a beautifully simple idea.

The ZPD is the sweet spot where a task is slightly too difficult for a child to complete alone but is achievable with guidance from a more knowledgeable person—a teacher, parent, or even a peer.

Real-World Example: A child learning to tie their shoes might struggle alone but can succeed when a parent guides their hands through the "bunny ears" motion. That supportive guidance is the key that unlocks the new skill.

Vygotsky's emphasis on social interaction perfectly complements Piaget's work on individual discovery. Together, they give us a holistic view of a learner who builds knowledge both internally and through connections with the world around them.

Constructivist Learning in the Real World: Practical Examples

So, what does constructivist learning theory actually look like in a classroom or at home? It's less about a teacher lecturing and more about a facilitator creating an environment ripe for discovery.

Let's consider a science lesson on electrical circuits. In a traditional setting, students might read a textbook chapter and label a diagram. In a constructivist classroom, they'd get a box with batteries, bulbs, and wires and a challenge: "Figure out how to make the bulb light up."

This small shift changes everything. Students aren't just memorizing a definition; they are experiencing the principles of electricity firsthand. They test hypotheses, learn from failures, and build their own mental model of how a circuit works based on direct, personal experience.

From History Books To Lived Stories

This hands-on approach isn't limited to STEM. Imagine a history class learning about a major historical event. Instead of just listening to a lecture, students could be tasked with creating a short documentary.

This project-based learning forces them to:

- Dig through primary sources like letters and photographs.

- Debate different interpretations of events with classmates.

- Construct a compelling narrative that presents their conclusions.

They become active historians, not passive recipients of facts. This method of active engagement is critical for deep learning, as explored in our guide on the benefits of hands-on learning.

A constructivist approach transforms learning from a spectator sport into an immersive, hands-on game. The goal isn't just to know the answer but to understand why it's the answer through direct experience.

Bringing Constructivism Home with Actionable Tips

This powerful learning philosophy thrives at home. It happens anytime a child is encouraged to experiment, ask questions, and learn from the results.

Hands-on science kits, like a build-your-own volcano, are perfect examples. When a child mixes baking soda and vinegar, they are:

- Forming a hypothesis about what will happen.

- Observing a chemical reaction with their own eyes.

- Drawing conclusions based on the fizzy result.

Each step is a small but powerful act of knowledge construction. These playful experiments empower kids to see themselves as capable scientists. By providing tools for discovery, parents can nurture a child's natural curiosity and help them build a strong, lasting foundation of knowledge.

The Pros and Cons of a Constructivist Approach

Why should parents and educators embrace this student-led model? The benefits are significant, fostering skills that last a lifetime. However, it's also important to acknowledge potential challenges.

Pros: Key Benefits of Constructivist Learning

- Develops Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving: Instead of just recalling facts, constructivism challenges kids to find the answers. When building a block tower, a child is analyzing stability, testing hypotheses ("What if I use a wider base?"), and learning from every collapse. This process builds resilience and a curious mindset.

- Boosts Engagement and Motivation: Learning is more fun when it's personal. When kids see how a math concept helps them design a model car or how a history lesson connects to their hometown, their interest soars. This active role fuels intrinsic motivation—the drive to learn for the joy of it, not just for a grade. Spark this excitement with ideas from our guide on how to increase student engagement.

- Builds Collaboration and Social Skills: Much of constructivist learning happens in groups. As kids team up on projects, they learn to communicate clearly, respect different perspectives, negotiate roles, and work toward a common goal. These are essential skills for school, work, and life.

Cons: Potential Challenges

- Time-Consuming: Inquiry-based projects can take more time than direct instruction, which can be a challenge in curriculum-heavy schedules.

- Difficult to Assess: Standardized tests may not capture the deep conceptual understanding gained through constructivist methods, making assessment more complex.

- Requires Skilled Facilitation: The teacher's role is more demanding. It requires expertise in guiding discovery without giving away the answers.

Despite these challenges, the long-term benefits of creating adaptable, curious, and resourceful learners often outweigh the drawbacks.

Common Questions About Constructivist Learning

Even with a clear understanding of the theory, parents and educators often have practical questions. Let's tackle some of the most common ones.

Is This Just Unstructured Playtime?

No, this is a common misconception. While play is a key component, constructivism is about guided discovery, not a free-for-all. The facilitator's role is to structure the environment with intriguing materials and pose strategic questions.

For example, while a child builds with blocks, a facilitator might ask, “That’s a tall tower! What do you think would happen if you used a wider base?” This prompt encourages the child to think about stability and engineering, turning simple play into a profound learning moment.

The facilitator's role is to be the "guide on the side," not the "sage on the stage." Their job is to pose challenges and ask questions that deepen a child’s thinking, rather than simply providing answers.

Does This Method Work for Every Subject?

Absolutely. The core principles of constructivism—active engagement and making connections—are universal. They can be applied to any subject.

- In Math: Instead of worksheets, students could design their dream bedroom on graph paper, applying concepts of area and perimeter in a creative, meaningful context.

- In Literature: Instead of a standard book report, students could stage a mock trial for a character, forcing them to dig for textual evidence and build a persuasive argument.

The goal is to create experiences where students grapple with the concepts themselves, which builds deep understanding in any discipline.

What Is the Teacher's Role in This Model?

In a constructivist classroom, the teacher transforms from the primary source of information into a facilitator of learning. Their focus shifts to designing engaging experiences, curating resources, and fostering a culture where questions are celebrated.

They observe students to understand their thought processes and ask probing questions to challenge their reasoning. This approach empowers students to take ownership of their learning journey. It's also a great fit for different learning styles, such as the hands-on approach detailed in our guide to what is the kinesthetic learning style.

How Can I Use Constructivism at Home?

Bringing constructivist learning home is easier than you might think. It starts with a simple mindset shift: stop providing answers and start asking good questions.

When your child asks "why," try turning it back to them: "That's a great question! What do you think?" This encourages them to develop their own theories. Suddenly, everyday activities become learning opportunities. Cooking becomes a chemistry lesson. A walk in the park is a biology field trip. Building a couch fort is an engineering project.

Ready to bring the power of hands-on, constructivist learning into your home? At Playz, we design science kits and toys that turn curiosity into knowledge. Explore our collection and watch your child build their understanding, one amazing discovery at a time.